Chapter 1: The Old Country

The journey of the McGinnis family to America did not begin in Ireland. It began an unknown number of years before, when on an uncertain date the Celts came to what would become Ireland. Or perhaps even before that.

We can track or ancestery back to an individual in the 18th century, but before that we have only history and Ireland so that is where we will begin.

Once Upon An Island There Was A Celt

The Turoe Stone (c. 100 BC), County Galway. Its intricate La Tène spirals testify to Celtic artistic sophistication.

The Turoe Stone (c. 100 BC), County Galway. Its intricate La Tène spirals testify to Celtic artistic sophistication.There’s an increasing school of thought that Celtic civilization was not a separate race but rather a language and a way of life that spread from one people to another. There was no mighty invasion, just a steady influx of Celtic people crossing from Britain and the mainland over the centuries.

The very earliest Celtic speakers may have journeyed to Ireland as early as 1000 BC. ~1000 BC - King David rules Israel; the Trojan War is a recent memory They developed an independent Gaelic society that allowed the Ulster inhabitants to survive not just from the Celts but also from those who preceded them in the earliest times. The Romans, notably, never crossed over to Ireland. ~44 BC - Julius Caesar is assassinated in Rome We cannot claim any close ties to them, at least not before or in the age of the Celts.

The entrance stone at Newgrange (c. 3200 BC), older than the pyramids. Ireland's people were carving spirals long before the Celts arrived.

The entrance stone at Newgrange (c. 3200 BC), older than the pyramids. Ireland's people were carving spirals long before the Celts arrived.Ireland is old by any judgment, and the further back we go, the greater variety of names we find for this mother country of ours. The poet Orpheus, in the time of Cyrus of Persia before Christ, called Ireland Iema. Aristotle called it Ierra. In the first century, Pomponius Mela called it Iuvemia. The Greek Plutarch called Ireland Ogygia, meaning “most ancient.” Caesar called it Hibernia, maybe from Irenia, likely from the Milesian king Heber. Eire or Eire-land became Ireland. It was the northmen and then the Saxons who used Ir-land in the 10th century.

The evolution of the Irish was influenced by the journeys of others. Phoenicians and every seafaring ship of all the empires called at Ireland’s ports in the first century. Commerce, merchants, and trading constantly exposed the Irish to good and bad exchanges with people from all over the world.

To give you an idea of the conglomerate of genes, looks, and traits we all can call ours: the Milesians, Anglo Normans, Firbolgs, Tuatha De Dananns, Gaels, Fomorians, Picts, Britons, Phoenicians, Greeks, Romans, Germans, Spanish, Albanians, Welsh, Scots, Fenians, Persians, Vikings, Norwegians, Danes, French, Italians, and Saxons. Just a sampling of tribes, nations, and peoples that touched Ireland in some way. There is little wonder that the mix of people on Ireland’s shores created an end product of people who are the worst and best of those who set foot on the old sod.

The Brian Boru Harp (14th-15th century), Trinity College Dublin. The model for Ireland's national symbol.

The Brian Boru Harp (14th-15th century), Trinity College Dublin. The model for Ireland's national symbol.Here’s a story that’s too old to prove but good enough to use: The Milesians, Eber and Eremon, divided the land of Ireland between themselves. Eremon got the north half and Eber the south. They also divided their followers, each getting an equal number of soldiers and the same number of every craftsman. After the dividing, there remained a harpist and a poet. The Milesians drew lots for them-the harpist to the north and the poet to the south-which accounts for the north being renowned for music and the south for song.

Some name us Irish as the Milesian Race because the Irish (Celtic) people were descended from Milesius of Spain. His sons, say historians, journeyed to Ireland in an invasion by which they took Ireland a thousand years before Christ. This account is so old there are those today who question the dates.

Whenever they traveled to Ireland, the Celtic wave from Europe crossed to England and Ireland, likely before Christ. The Celtic hordes were rough and warlike but were an organized people with a single king. Art and the skills to work stone were evident in these people as early as 900 BC. They had iron tools, which they used in mining and agriculture.

The McGinnis Name Emerges in the Fifth Century

At this point we skip forward a few hundred years to when the name McGinnis and all closely allied names with the same root emerged. ~400s AD - The Roman Empire falls; St. Patrick converts Ireland to Christianity

In a publication entitled Irish Pedigrees or the Origin and the Stem of the Irish Nation, John O’Hart wrote of MacGinnis of County Armagh: “Sir Arthur Magennis of Rathfriland in 1623 became the first Viscount Iveagh, County Down. 1623 - The Pilgrims have been at Plymouth Rock for three years The Irish families MacAongheris (of which MacGuinnes, Mac Ginnis, Magennis and McGinnis are some of the anglicized forms) were ancient Lords of Ineagh, a territory in Dál nAraidi, now the County Down in Ulster.”

At one time, 16 different versions of the ancient Ulster surname MagAonghusa were recorded. It means “son of Aonghus.” The ancestry goes back to a fifth-century chief of Dál Araidhe. The lords had their fortress at Rathfriland in Down. Magennis of Iveagh was created Viscount. Ruins of this early fort are still visible at Rathfriland.

The surviving wall of Magennis Castle (1611), Rathfriland, County Down. The McGinnis lords ruled from here for 400 years.

The surviving wall of Magennis Castle (1611), Rathfriland, County Down. The McGinnis lords ruled from here for 400 years.400 Years of Rule

It’s clear that the McGinnis name represented 12th-century lords in Iveagh who ruled County Down in Ulster from their stronghold in Rathfriland for 400 years. ~1100s-1500s - The Crusades; Magna Carta signed; Columbus reaches America They finally lost their land when they fought the English again in the 17th century.

In 1607, O’Neill was finally forced to give in to the English forces in the Nine Year War. 1594-1603 - Shakespeare writes his greatest plays; the Spanish Armada defeated O’Neill is reported to have married Catherine, daughter of MacGuiness, lord of Iveagh. O’Neill and MacGuiness and the lords’ sons and other relations-more than ninety souls at the war’s end-made what was referred to as the “Flight of the Earls.“ 1607 - Jamestown, Virginia founded the same year

John Behan's Flight of the Earls memorial (2007), Rathmullan. The bronze figures depict the earls boarding the ship that would carry them into exile.

John Behan's Flight of the Earls memorial (2007), Rathmullan. The bronze figures depict the earls boarding the ship that would carry them into exile.On September 14, 1607, they boarded a ship at Rathmullan on Lough Swilly and departed Ireland forever. Tadhg Ó Cianáin, a chronicler who traveled with the exiles, kept a diary-the only eyewitness account we have:

The first night was bright, quiet and calm, with a breeze from the south-west.

Lough Swilly near Rathmullan, County Donegal. From this shore, the earls sailed into exile in 1607.

Lough Swilly near Rathmullan, County Donegal. From this shore, the earls sailed into exile in 1607.They sailed for France and finally to Rome, where the Pope gave them a pension. The Annals of the Four Masters, compiled just 25 years later by Franciscan monks who saw this as the death of Gaelic Ireland, recorded the departure with anguish:

Woe to the heart that meditated, woe to the mind that conceived, woe to the council that decided on the project of their setting out on the voyage!

The Nine Years War was Ireland’s last stand, under known laws, against England and English Law.

The Elizabethan Wars ended. Ireland in the 17th century saw the overthrow of the clan and communal system, the destruction of the Great Gaelic Houses, and the establishment of centralization by a despotic power.

The bardic poets-the learned class who had served the Gaelic lords for centuries-captured the devastation. Fearghal Óg Mac an Bhaird, writing from exile in Louvain where he would die in poverty, mourned the collapse of everything he knew:

We are a poor flock without a shepherd. Caffar, head of Erin’s honour, lies beneath a gravestone-what sadder fate?-Away in Italy.

When Hugh O’Neill himself died in Rome in 1616, the Four Masters chose his death as the final entry in their Annals-a deliberate statement that Gaelic Ireland had died with him:

The person who here died was a powerful, mighty lord…The person who here died was a powerful, mighty lord, endowed with wisdom, subtlety, and profundity of mind and intellect; a warlike, predatory, enterprising lord, in defending his religion and patrimony against his enemies.

Perhaps most haunting is the lament composed by Eoghan Ruadh Mac an Bhaird, addressed to Nuala O’Donnell as she mourned at her brothers’ tomb in Rome. The scholar Eleanor Knott called it “the noblest and most moving of all the known elegies in the classical style.” James Clarence Mangan later translated it as “O Woman of the Piercing Wail”:

O Woman of the Piercing Wail, who mournest o’er yon mound of clay…O Woman of the Piercing Wail, Who mournest o’er yon mound of clay With sigh and groan, Would God thou wert among the Gael! Thou wouldst not then from day to day Weep thus alone. ‘Twere long before, around a grave In green Tirconnell, one could find This loneliness; Near where Beann-Boirche’s banners wave Such grief as thine could ne’er have pined Companionless.

John Speed's map of Ulster (1610). The Plantation would transform this landscape, replacing Gaelic lords with English and Scottish settlers.

John Speed's map of Ulster (1610). The Plantation would transform this landscape, replacing Gaelic lords with English and Scottish settlers.Within a decade, the crown sought to “plantationize” Ulster with Scots and English. 1609 - The Pilgrims will land at Plymouth Rock in eleven years The Irish considered the vast influx of Scots pushed into Ulster to be “wholesale robbing” of the clans. Some four million acres were confiscated. The English wanted the rich soil for crops and the harvest for England. The native farmers lost land that had been theirs since the island was first settled.

The settlers saw it differently. Thomas Blennerhasset’s 1610 pamphlet promoted the Plantation with evangelical fervor:

Art thou a minister of God’s word? Make speed, the harvest is great, but the laborers be fewe.

By 1622, surveys recorded that the largest Scottish-founded town, Strabane, had “more than one hundred houses” and its inhabitants were “very industrious and do daily beautify their town with new buildings, strong and defensible.” For the dispossessed Irish watching strangers build on their ancestral land, this was the new reality.

The 1641 Uprising

Sir Phelim O'Neill (c. 1604-1653), who led the 1641 uprising alongside Magennis and other Ulster lords.

Sir Phelim O'Neill (c. 1604-1653), who led the 1641 uprising alongside Magennis and other Ulster lords.The dispossessed Irish did not accept this new reality quietly. In 1641, they rose up to reclaim their land. 1641 - The English Civil War begins the following year On October 23, leaders of the old Ulster families-Phelim O’Neill, Magennis, O’Hanlon, O’Hagan, MacMahon, McGuire, O’Quinn, O’Farrell, O’Reilly-led their cohorts, wild-eyed, staunch, and determined to rid the Scots of their Irish land. In a few hours they made Ulster their own again. Practically in one night they re-conquered their province. The planters scurried to the few cities they still held force over.

This Magennis may or may not be in my line or yours, but it is representative of the name in Ulster. I might just claim this determined fighter to be kin to us, though I have no evidence one way or another. It is clear that the name was in Ireland before the Scots came. McGinnis is Old Irish.

But the uprising failed. More battles and more give-and-take for power and control followed, but the Plantation held. The settlers stayed. And more kept coming.

The Scots Who Came to Ulster

Who were these settlers that the Irish had tried to drive out? They were not simply “English” or “British.” The vast majority were Lowland Scots-Presbyterian farmers and craftsmen from the Scottish borderlands: Ayrshire, Dumfries, Galloway, Lanarkshire, and the Scottish Borders. 1606-1640 - Approximately 100,000 Lowland Scots migrate to Ulster By 1620, as many as 50,000 had crossed the narrow North Channel to Ulster. Another 50,000 followed by 1640.

The Lowland Scots Migration to Ulster (1606-1640)

They were Presbyterians-followers of John Knox’s stern Calvinist tradition-and this faith set them apart from both the Catholic Irish natives and the Anglican English establishment. The English crown wanted Protestant settlers to pacify Ulster, but they got more than they bargained for. These Scots were no more loyal to Anglican bishops than to Catholic ones. They brought with them a stubborn independence, a belief that each congregation should govern itself, and a suspicion of any authority-religious or political-that tried to tell them what to believe.

In Ulster, the Scots prospered for a time, building farms and towns and churches alongside the dispossessed Irish. But they were never fully welcome by the English authorities either. The Penal Laws that punished Catholics also restricted Presbyterian rights. Presbyterians could worship, but they faced discrimination in politics, education, and land ownership. They were caught between: too Protestant for Catholic Ireland, too Presbyterian for Anglican England.

A Changed Ulster

Over the generations that followed, something unexpected happened. The lines between Old Irish and Scots settler began to blur. They were neighbors, then trading partners, then perhaps in-laws. Faiths shifted. Identities merged. The McGinnis family-Old Irish Catholics who had once ruled County Down-found themselves living alongside these Scottish Presbyterian settlers. By the time our ancestors left for America, they appear to have been Presbyterian themselves.

We cannot trace exactly when or how this happened. But we know the endpoint: Charles McGinnis, our earliest confirmed ancestor, appears in the records of a Presbyterian church in North Carolina. Somewhere along the way, the family that had once ruled Catholic Iveagh became part of the Presbyterian exodus to America. Whether by conversion, by marriage, or by the slow erosion of old identities in a changing Ulster, the McGinnises became what the Americans would call “Scots-Irish.”

In the 1600s and on into the 1700s, the situation remained difficult in Ireland for everyone-Old Irish and Scots settler alike. But in the north, families with modest holdings could look at funding passage on boats bound for America. Selling their small landholdings was a ticket to travel.

Tempted to Risk It All

County Down, Armagh, and other adjacent counties were mostly agricultural, with linen weaving a distant second in the early years. By mid-1700s, linen was the key economic activity for that region of Ulster. 1700s - Bach and Handel compose; the Enlightenment flourishes Recessions resulting from poor crop years, livestock problems, or market problems at the buyer’s home were always a threat.

Rents climbed as land got scarce. The people of Ulster sold land or rights to land to get capital for emigration. Landholding units in the province practically doubled from 1718 to 1775. 1718-1775 - The American colonies grow restless; revolution looms More of the people were doing better than 100 years before. Incomes were up in Ulster.

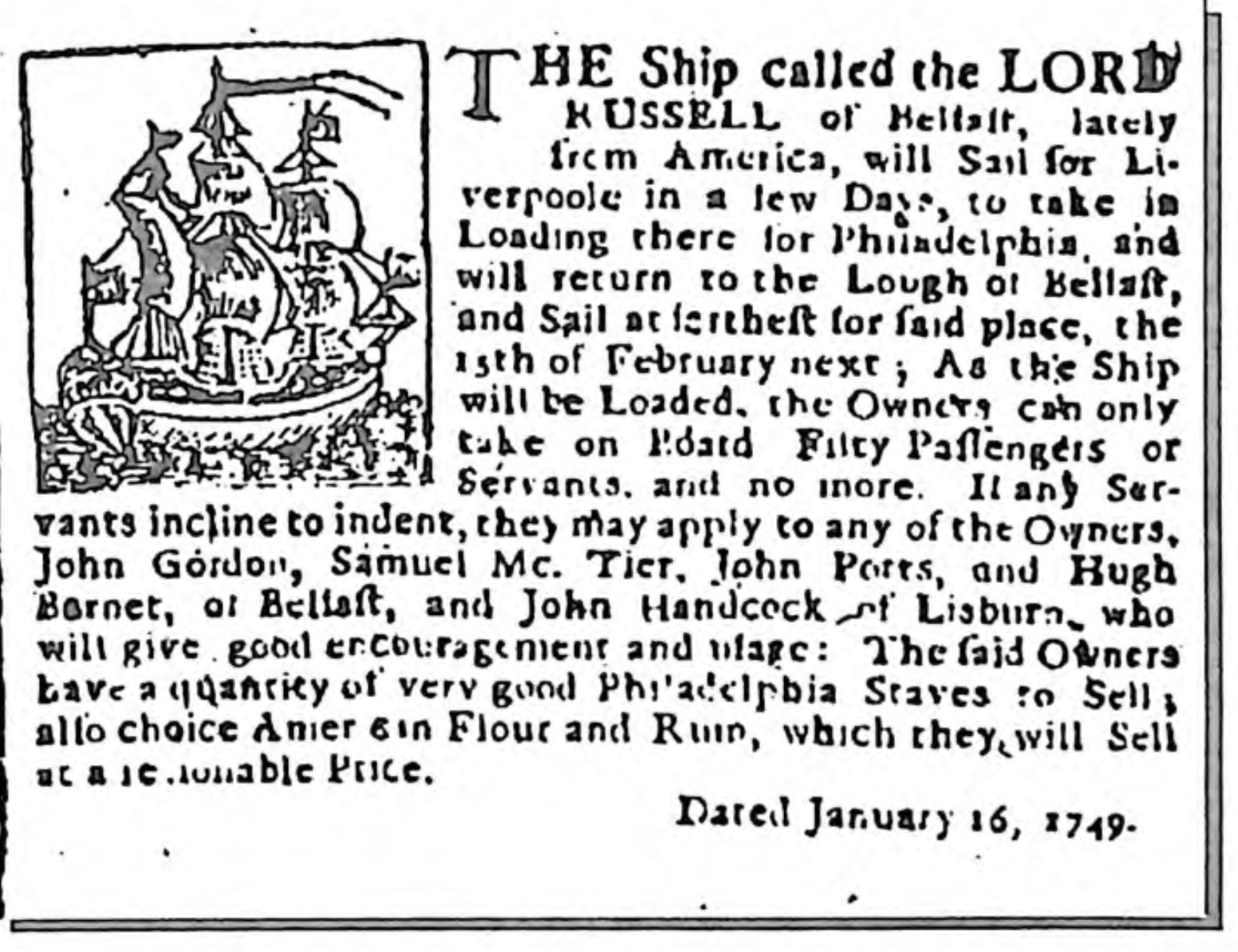

The stimulus for emigration created by land and rents was pushed forward in their minds by the presumed advantage of “better” situations in America. Ads in newspapers and flyers extolled the “goodness” in America. Ship agents hyped the reasons to sign on board. Captains and crews of ships hawked the benefits in America-“Sign up today.” Letters from friends and relatives already in America told of how much better “Philly” was than Newry or Belfast.

The stimulus for emigration created by land and rents was pushed forward in their minds by the presumed advantage of “better” situations in America. Ads in newspapers and flyers extolled the “goodness” in America. Ship agents hyped the reasons to sign on board. Captains and crews of ships hawked the benefits in America-“Sign up today.” Letters from friends and relatives already in America told of how much better “Philly” was than Newry or Belfast.

We have one such letter. In 1725, Robert Parke, an Irish Quaker who had emigrated the year before, wrote to his relatives back in Ireland urging them to make the crossing:

There is not one of the family but what likes the country very well…There is not one of the family but what likes the country very well and wod If we were in Ireland again come here Directly it being the best country for working folk & tradesmen of any in the world, but for Drunkards and Idlers, they cannot live well any where.

We have not had a days Sickness in the family Since we Came in to the Country, Blessed be god for it. My father has not had his health better these ten years than since he Came here.

Land is of all Prices Even from ten Pounds to one hundred Pounds a hundred, according to the goodness or else situation thereof, & grows dearer every year by Reason of Vast Quantities of People that Come here yearly from Several Parts of the world.

“Make what Speed you can to Come here,” Parke urged. “The Sooner the better.”

While Presbyterians were thought to be the largest group to ship out, a goodly number of Irish Catholics and adherents of the Established Church, who were of English descent, also came over in the 1700s. Irish classified as “Old Irish”-seemingly not mixed with the Scots or English-were also on the ships. The McGinnis name was Old Irish-but by this point, the distinction between “Old Irish” and “Scots-Irish” had blurred for many families in Ulster.

This was the world our McGinnis ancestors knew. A name that once meant lordship over County Down, now just another family scraping by in a changed Ulster. The old Gaelic order was gone. The Scottish settlers had become neighbors, then perhaps in-laws. The Presbyterian faith that the Scots brought with them had taken root in families that had once been Catholic. And now, together, they were all looking west.

Five great waves of emigration would bring over 200,000 people from Ulster to the American colonies between 1717 and 1775. The largest waves came in 1717-18, 1725-29, 1740-41, 1754-55, and 1771-75-each triggered by crop failures, rent increases, or religious persecution. Most landed at Philadelphia, where they became known as the “Scotch-Irish”-an American term that distinguished them from the Catholic Irish who would arrive in later centuries. In Britain and Ireland, they called themselves Ulster Scots. But whatever the label, they were people who had been uprooted once already, from Scotland to Ulster, and were now being uprooted again.

The McGinnises were among them. We do not know exactly when our ancestor crossed the Atlantic, or on which ship. But we know where he ended up: in the records of a Presbyterian church in North Carolina, listed as “Charles McGinnis, Colonel, PA.” An Old Irish name. A Presbyterian faith. An American future.

The journey to America was about to begin.

Chapter Navigation

← Guide Home | Next: The Crossing →

References

McGinnis, Richard W. (2003). 1700-2003 My McGinnis History Begins to Fit: An old Irish family from Ulster comes to North Carolina and then to Georgia. Compiled with assistance from Sharon Tate Moody, CGRS.

“Magennis.” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Magennis. The Magennises were lords of Iveagh in County Down from the 12th century, with the earliest charter reference in 1153.

“The Barony of Iveagh.” Library Ireland, https://www.libraryireland.com/articles/baronyiveaghjol/. Details the territorial extent and governance of the McGinnis/Magennis lordship.

Ó Cianáin, Tadhg. Imeacht na nIarlaí (The Departure of the Chiefs). Contemporary diary of the Flight of the Earls, the only continuous eyewitness account of the 1607 departure.

“Flight of the Earls.” Ask About Ireland, https://www.askaboutireland.ie/reading-room/history-heritage/history-of-ireland/the-flight-of-the-earls-1/. On September 4, 1607, O’Neill and more than ninety followers sailed from Rathmullan in Donegal.

“Plantation of Ulster 1609-1690.” Historical overview of the systematic settlement of Ulster with Scottish and English Protestant colonists following the Flight of the Earls.

“Today in Irish History - First Day of the 1641 Rebellion, October 23.” The Irish Story, https://www.theirishstory.com/2010/10/23/today-in-irish-history-october-23-first-day-of-the-1641-rebellion/. The rebellion began on October 23, 1641, led by Catholic gentry and military officers.

“Nine Years’ War (Ireland).” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nine_Years%27_War_(Ireland). The war ended with the Treaty of Mellifont on March 30, 1603.

“Catherine O’Neill, Countess of Tyrone.” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Catherine_O%27Neill,_Countess_of_Tyrone.

“Magennis, Arthur.” Dictionary of Irish Biography, https://www.dib.ie/biography/magennis-arthur-a9276. Sir Arthur Magennis was created Viscount Magennis of Iveagh in 1623 by King James I.

O’Donovan, John, ed. and trans. Annála Ríoghachta Éireann: Annals of the Kingdom of Ireland by the Four Masters. 7 vols. Dublin, 1851. The authoritative scholarly edition with English translation. Available at https://www.askaboutireland.ie/reading-room/digital-book-collection/digital-books-by-subject/history-of-ireland/odonavan-annals-of-the-fo/

Mac an Bhaird, Fearghal Óg. “Mór an lucht arthraigh Éire” (Great the company that changed Ireland). Composed c. 1607-1608 in exile. See https://celt.ucc.ie/published/G402130.html

Mac an Bhaird, Eoghan Ruadh. “A bhean fuair faill ar an bhfeart” (O Woman of the Piercing Wail). Elegy for the Ulster lords, c. 1608. Edited with translation in Knott, Eleanor. “Mac an Bhaird’s elegy on the Ulster lords.” Celtica 5 (1960): 161-171.

“Mac an Bhaird, Fearghal Óg.” Dictionary of Irish Biography, https://www.dib.ie/biography/mac-bhaird-fearghal-og-a4988

Blennerhasset, Thomas. A Direction for the Plantation in Ulster. London, 1610. Promotional pamphlet for the Ulster Plantation.

“The Plantation of Ulster (1610-1630).” Discover Ulster-Scots, https://discoverulsterscots.com/history-culture/plantation-ulster-1610-1630. Includes excerpts from 1622 surveys.

Parke, Robert. Letter from Chester County, Pennsylvania, 1725. In National Humanities Center: Two Irish Settlers in America, 1720s-1740s, https://nationalhumanitiescenter.org/pds/becomingamer/growth/text4/irishpennsylvania.pdf

Miller, Kerby A., et al. Irish Immigrants in the Land of Canaan: Letters and Memoirs from Colonial and Revolutionary America, 1675-1815. Oxford University Press, 2003.

Dickson, R.J. Ulster Emigration to Colonial America, 1718-1775. Belfast: Ulster Historical Foundation, 2016 (reprint of 1966 edition).

The Scots-Irish

“The Plantation of Ulster (1610-1630).” Discover Ulster-Scots, https://discoverulsterscots.com/history-culture/plantation-ulster-1610-1630. Scotland’s first and ultimately most successful project of colonisation beyond its shores, when 20-30,000 Scots crossed the North Channel into Ireland.

“Who Are the Ulster-Scots?” Discover Ulster-Scots, https://discoverulsterscots.com/history-culture/who-are-ulster-scots. Scots-Irish, Scotch-Irish, and Ulster-Scots are variant names for the same people who left Scotland, settled in Ulster, and then moved on to North America.

“The Scotch-Irish & America - A Timeline.” Discover Ulster-Scots, https://discoverulsterscots.com/emigration-influence/america/scotch-irish-america. Documents the five great waves of emigration that brought over 200,000 Ulster Scots to America between 1717 and 1775.

“The Scots in Ulster.” Ulster Historical Foundation, https://ulsterhistoricalfoundation.com/the-scots-in-ulster/home. Scholarly resource on the migration of Lowland Scots to Ulster and their subsequent history.

Image Credits

Turoe Stone photograph via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA). National Museum of Ireland artifact, c. 100 BC.

Newgrange Entrance Stone photograph via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA). Office of Public Works, Ireland.

Brian Boru Harp (Trinity College Harp) photograph via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA). Trinity College Dublin.

Magennis Castle ruins photograph via Geograph/Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA).

Flight of the Earls Memorial sculpture by John Behan (2007), photograph via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA).

Rathmullan and Lough Swilly photograph via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA).

Ulster map by John Speed (1610), via Wikimedia Commons. Public domain.

Sir Phelim O’Neill portrait via Wikimedia Commons. Public domain.