The Art and History of General Dynamics' Atoms for Peace Campaign

I have no idea how I first stumbled across the striking modernist artwork of General Dynamics’ Atoms for Peace campaign. But somewhere along the way I did, and I’ve been fascinated by it ever since. I grew up in more of an art family than an engineering one, and in particular was a Kandinsky/Bauhaus kid. So not suprisingly, I was drawn to the Atoms for Peace work. But it also struck me as so incredibly weird. Why was a defense contractor doing this? What was the story behind it?

So here we are, a history of the Atoms for Peace campaign:

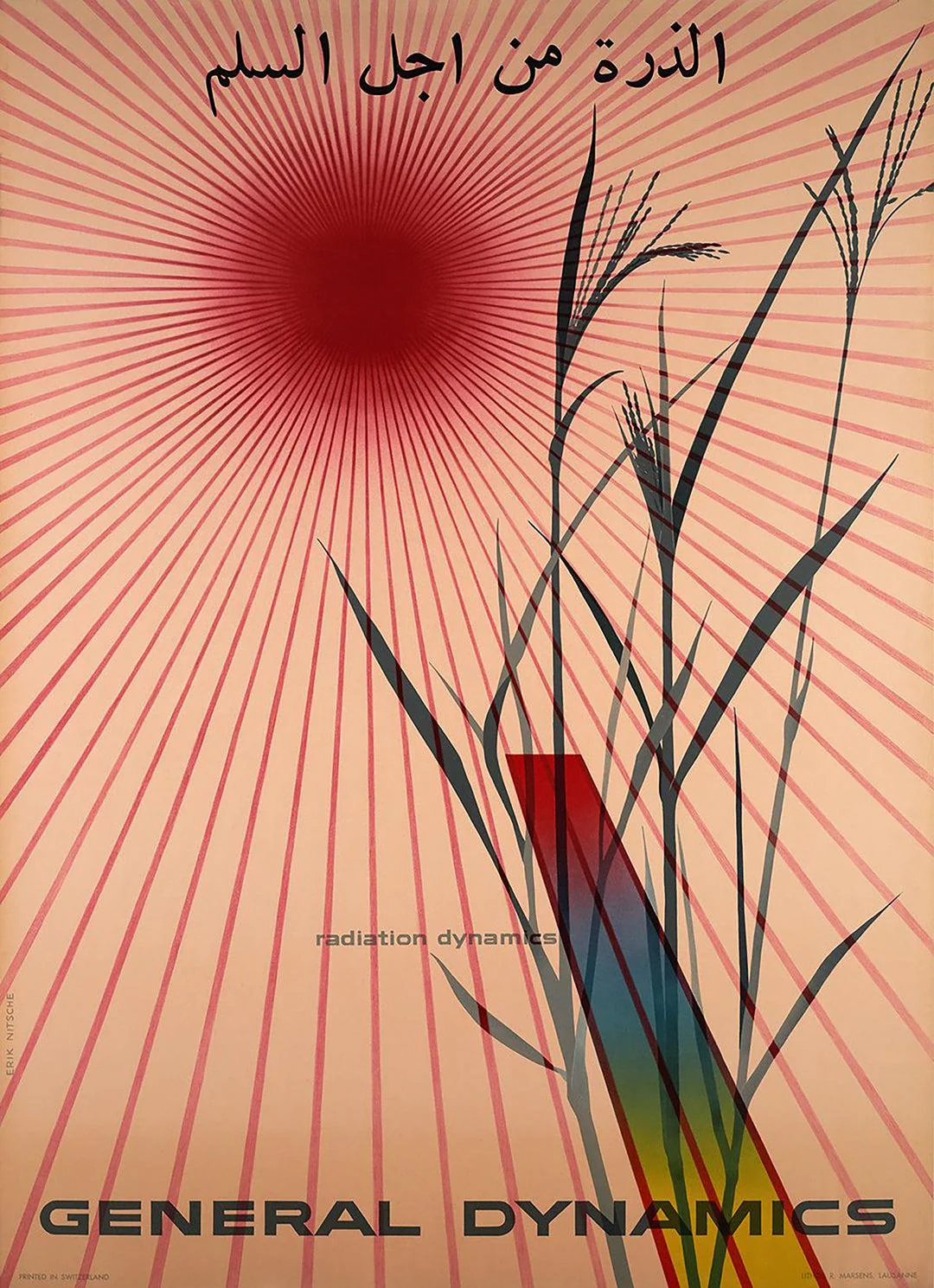

The striking modernist artwork of General Dynamics’ Atoms for Peace campaign stands as one of the most memorable corporate messaging efforts of the 1950s. Beyond its artistic legacy lies a complex story about nuclear energy, public perception, and the dawn of the atomic age.

Origins of Atoms for Peace

On December 8, 1953, President Dwight D. Eisenhower stood before the 470th Plenary Meeting of the United Nations General Assembly to address what he called “the fearful atomic dilemma.” In what would become known as the “Atoms for Peace” speech, he proposed transforming atomic power from a force of destruction into a benefit for mankind. This pivotal moment marked a shift in public discourse around nuclear technology, taking it beyond government laboratories and military applications into the public consciousness.

Erik Nitsche: The Artist Behind the Campaign

Erik Nitsche’s relationship with General Dynamics began in 1953, the same year as Eisenhower’s landmark speech. A Swiss-born graphic designer, Nitsche had already established himself through his work for avant-garde European publications and major American magazines like Life, Town and Country, and Vanity Fair. His appointment as Art Director in 1955 would lead to one of the most innovative corporate rebranding exercises of the era.

What made Nitsche’s work particularly significant was its global reach. The posters were created specifically for promoting nuclear energy in foreign countries, with text carefully translated into multiple languages including English, French, Japanese, Hindi, Russian, and German: nations committed to peaceful atomic energy development. This international approach aligned perfectly with Eisenhower’s vision of atomic power as a tool for global cooperation.

The Art and Design

The design elements of Nitsche’s campaign were revolutionary for their time, born partly from necessity and partly from artistic vision. As Art Director from 1955 to 1960, Nitsche faced an interesting constraint: he was barred from depicting specific General Dynamics products, many of which were classified defense projects he wasn’t even allowed to see. This limitation pushed him toward abstraction, ultimately leading to one of the most influential corporate advertising campaigns of the twentieth century.

The campaign’s visual language was characterized by several key elements:

- Clean Compositions: Nitsche employed pared-down, minimalist layouts that created a distinctly modern look, drawing from his background in the Swiss Style of the 1930s.

- Typography as Design: Text was treated as an integral design element, with simplicity that complemented the overall clean, modern aesthetic.

- Modernist Influences: The artwork borrowed heavily from the Modern Art movement to evoke dynamism and innovation.

- Symbolic Approach: Unable to show actual products, Nitsche created abstract representations of atomic energy’s peaceful potential.

Corporate Strategy and Context

In 1955, General Dynamics found itself at a critical juncture. As a newly formed parent company overseeing eleven manufacturers, it was at the forefront of America’s nuclear deterrence strategy. The company had achieved significant technological milestones, including manufacturing the first atomic submarine, the Nautilus, and securing a commission to build the first atomic airplane.

But this success created a unique corporate communications challenge. John Jay Hopkins, General Dynamics’ president, sought to reposition the company’s public image away from war and destruction toward peace and prosperity. This was complicated by the classified nature of their work, many of their most impressive achievements couldn’t be shared with the public.

The 1955 International Conference on the Peaceful Uses of Atomic Energy in Geneva presented both an opportunity and a challenge. While General Dynamics was technologically ahead of many competitors, their inability to showcase actual products due to security classifications put them at a disadvantage. The company needed to find a way to elevate its reputation to match better-known corporations like General Electric and Westinghouse without revealing classified information.

Legacy and Impact

The enduring significance of Nitsche’s work is evidenced by its continued exhibition and study. Today, these lithographic public-relations-oriented fine art prints are preserved and displayed in museums, with exhibitions typically featuring fifteen 30" x 55" framed artist’s posters. The campaign’s influence extended far beyond corporate communications: its visual language became synonymous with the atomic age’s vision of an idealistic future.

The success of the Atoms for Peace campaign demonstrates how artistic innovation can transcend commercial objectives. What began as a corporate rebranding exercise evolved into a defining aesthetic of an era, influencing everything from industrial design to popular culture. More importantly, it showed how design could help bridge the gap between complex technological advancement and public understanding, creating a visual language for the atomic age that emphasized hope over fear.

While initially drawn to this topic by the striking aesthetics of Nitsche’s work, researching it has led to deeper reflections on Eisenhower’s vision and our progress toward it. His words still resonate today: “the miraculous inventiveness of man shall not be dedicated to his death, but consecrated to his life.” Nuclear energy now provides about 10% of the world’s electricity from about 440 power reactors. This suggests some progress toward his peaceful vision. Yet the reality of nuclear proliferation tells a more complex story. As of 2024, nine nuclear-armed states possess an estimated 12,121 warheads, with several nations actively expanding their arsenals and developing new delivery systems. SIPRI’s assessment that “we have not seen nuclear weapons playing such a prominent role in international relations since the cold war” suggests we’ve drifted far from Eisenhower’s aspirations.

Perhaps this tension between hope and reality was itself part of Nitsche’s artistic intention. His abstract compositions, hovering between scientific precision and artistic ambiguity, mirror our own complex relationship with atomic power: a technology that continues to embody both tremendous promise and sobering responsibility. As geopolitical tensions rise and nuclear arsenals grow, Nitsche’s posters serve not just as artifacts of mid-century optimism, but as poignant reminders of an unrealized dream: that humanity’s mastery of the atom might truly be consecrated to life rather than death.

Stay in the loop

Get notified when I publish new posts. No spam, unsubscribe anytime.